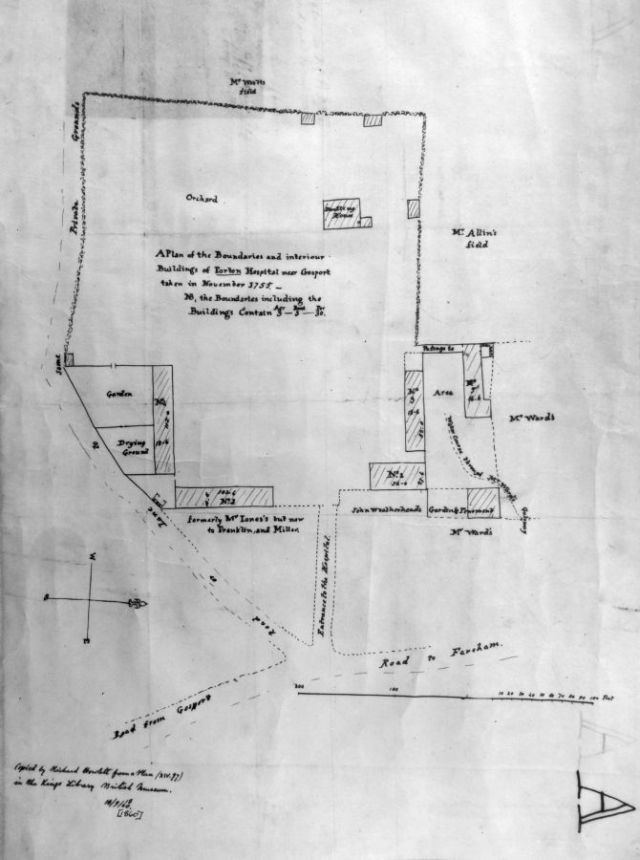

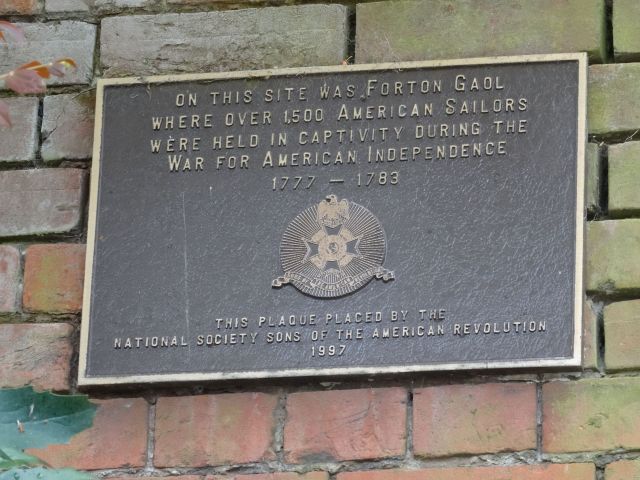

A prison existed at Forton as early as 1777, (and probably earlier during the Seven Years War according to the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography), when the old ‘Fortune Hospital’ was used to confine supporters of the American revolution. The hospital, described as ‘a shambles no more than a clutter of tumbledown shacks, I doubt if anyone actually got better through the nursing they received there’, was an unhealthy straggle of wooden huts and unsightly buildings. Most written sources state that it was erected in 1713 (but it is possible that it was there much earlier) on a marshy site where nowadays Leesland Road meets Lees Lane. A merchant called Nathaniel Jackson won a contract from the Admiralty board to provide accommodation and medical facilities for naval and military men from the Portsmouth area. He seems to have been more interested in making money than providing health care as he paid the medical staff a pittance, thus attracting second rate doctors, and erected buildings of a poor nature. The hospital was to provide beds for 700 sailors from the Royal Navy. After he died (1716?) without issue Nathaniel Jackson’s widow, Mary Burrow, claimed ownership of a great number of beds and sheets with other furniture in proportion for the great number of seamen who were invalids and who by the direction of the government were received and taken care of in this house. In 1725 the Lord Chancellor ruled that she could have them but on appeal to the House of Lords the decision was reversed. Some written histories and websites state that the site of the hospital became the Forton Barracks but it is certain from written evidence and plans that it became Forton Prison.

Writing in Yankee Sailors in British Gaols: Prisoners of War at Forton and Mill, 1777-1783 Sheldon Samuel Cohen describes the origins of the Gaol thus:

Forton Gaol had developed from these Hampshire surroundings well before the American War for Independence. However, when construction began at the crossroads hamlet in 1713, the buildings were intended for a hospital, not a prison. This fact was clearly evident in part of a legal statement involving the merchant and land speculator Nathaniel Jackson: Mr. Jackson was before his marriage and at the time of his death possessed of a hospital called Forton Hospital near Gosport which he employed in entertaining of sick and wounded Seamen of the Royal Navy, by contract with the Commissioners for Sick and Wounded Seamen, and which for that purpose was furnished with men near 700 beds and other furniture for such a service and not for private use. With the passage of time and recurrent medical shortcomings at this facility, a new, better-situated hospital for royal seamen, called Haslar. was built immediately south of Gosport. After its opening in 1753, Haslar was used more frequently for ailing British mariners, so that with the large influx of prisoners during the Seven Years War, Forton found itself converted into a detention centre.

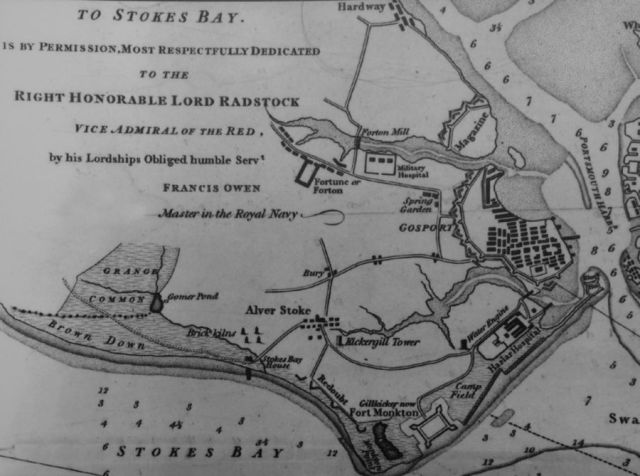

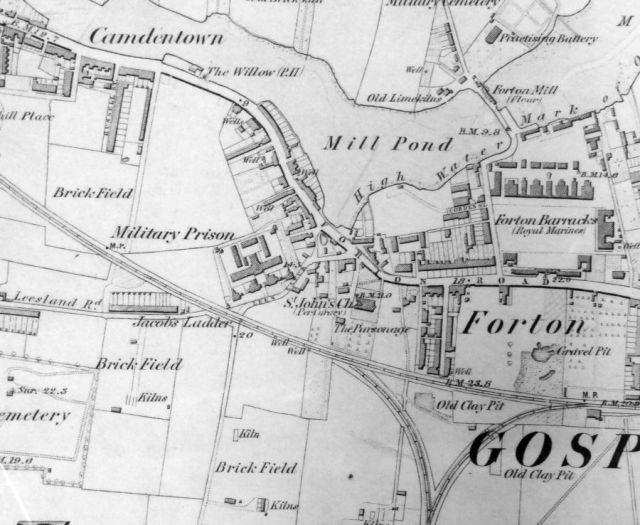

Extant maps and personal accounts offer good descriptions of Forton’s physical features about the time it was reopened as a prison in June 1777. The main entrance to the facility lay at the end of a pathway off the Gosport-Fareham Road. The prison grounds comprised a total of about three and one-half acres surrounded mainly by farm fields and private estates. The structures, aside from administrative quarters, consisted principally of two spacious buildings which reportedly could hold up to two thousand inmates. During the war in America, one building was used for lower rank captives and one for higher officers. (No parole opportunities within Britain were provided, in contrast to the practice adopted for officers of recognized foreign powers. As a result, these men at first were kept in the same prison area as their crewmen.) There was one airing ground situated between Forton’s two main buildings and another nearby, reportedly on three quarters of an acre of level ground. In December 1777. the Admiralty approved the construction of a shed on this airing ground; it was open on all sides, and seats were placed under it to sit on during hot or sultry weather. Eight-foot-high iron pickets driven into the ground about eight inches apart surrounded the entire area. Soon after the prison was reopened, the Commissioners for Sick and Hurt Seamen wrote the Admiralty recommending that chevaux-de-frize (iron spikes) be placed on the walls of Forton’s confinement buildings, but evidently this escape deterrent was not added. Sanitation requirements were not a problem; drainage and disposal were expedited by the proximity of Forton Lake about two hundred feet away, on the opposite side of Fareham Road.

A mass escape involved fifty seven prisoners who tunneled their way out and disappeared into the countryside. Sheldon Cohen records that there was a delay in opening the prison although it was ready for use in May 1777, due to technicalities which were solved with the assistance of Admiral Pye, Portsmouth’s naval director. On June 13 1777 the Commission for Sick and Hurt Seamen wrote to the Admiralty that Fort was ready to accept inmates. That same day the first American seamen were confined there. By November 1782 a total of more than 1200 captured rebels had been listed on the rostas for the prison.

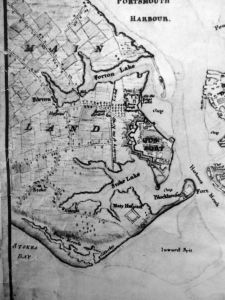

From circa 1777 to 1783 the old hospital was continuously used as a prison. Sheldon Samuel Cohen writing in ‘British Supporters of the American Revolution, 1775-1783’ tells of Forton Prison which was located across Portsmouth Harbour, approximately a mile northwest of Gosport Harbour, in the Parish of Alverstoke. Prison conditions were far from ideal for the first American inmates in 1777. Timothy Connor, among Forton’s earliest captives, noted that for a day after he and his shipmates arrived on June 13, they ‘had nothing to eat but boiled cabbage, which was part of the officers’ allowance’. The supply of provisions eventually improved, but the quality and quantity of food continued to be the subject of intermittent prisoner complaints. Clothing was another shortcoming; many of the early arrivals had had their possessions taken during their shipboard captivity, and some inmates arrived at Forton half-naked. Nevertheless, it was not until November 1777 that the Commission for Sick and Hurt Seamen dispatched a petition to the Admiralty asking them to alleviate the great want of clothing and of Shoes and Stockings amongst the prisoners.

A mass escape involved fifty seven prisoners who tunneled their way out and disappeared into the countryside.

Sheldon Cohen writes: The enterprising American prisoners dug tunnels (including one from the prison privy); they jumped the eight-foot prison pickets and dug under the fences; they bribed or tricked corrupt, ill-trained, or incompetent guards; and in a few cases they feigned serious illness in order to obtain transfer to the less protected Haslar Hospital. Punishment for recaptured fugitives, forty days in the Black Hole at half-rations, plus relegation to the bottom of the exchange list, was apparently not too serious a deterrent. Furthermore, Forton itself was less secure than Mill Prison and the area immediately outside the Gosport prison was more conducive to hiding than the Plymouth gaol. Moreover, guards at both Forton and Mill had no standing orders to fire at fleeing inmates. Therefore, escape must have seemed more feasible and attractive than a frustrating and tedious wait for exchange.

One of the American prisoners, Timothy Connor, wrote a song:

‘….and fortune’s Keep, a dread abode,

where, ‘neath misfortune’s heavy load.,

Ambition’s slaves , for despot’s crime,

Were captive kept in warlike time.’

Nathaniel Fanning a Yankee sailor captured by the frigate Andromeda writes in The Memoirs of Nathaniel Fanning 1778 to 1783 after being captured and sent to Portsmouth in 1788:

After we had got through with our examination, we were marched to Forton prison and there committed ‘for piracy and high treason.’ This prison lies about two miles from Portsmouth harbour and was built for an hospital in the reign of Queen Ann, for the accommodation of sick and wounded seamen. It is in two large spacious buildings, separate from each by a yard large enough to parade a guard of an hundred men, which number the officers and soldiers consisted of while I remained there a prisoner. The buildings thus separated, the northernmost was occupied by the under officers, sailors and marines; and the southern-most by the officers of somewhat higher grades. It is a very convenient place for prisoners of war, as there is a spacious lot adjoining the prisons containing about three-quarters of an acre of level ground, in the centre of which stands a large shed or building, open on all sides to admit the free circulation of air; under which were seats for our accommodation when the weather was hot and sultry. The large yard, to prevent the prisoners from escaping, was picketed in on all sides; these were planted in the ground about two inches asunder, and about eight feet long. It would be very easy for the Americans to make their escape from hence even in the daytime, were it not for the peasants, who were always lurking about here, followed by their great dogs, and armed with great clubs. The reader will observe, this was the fact with regard to the American prisoners; and upon the report of one of us having made his escape, I could see sometimes seventy or eighty in a few minutes in search of their booty, beating the bushes, running to and fro, from ditch to ditch, till they had got fast hold of the poor Yankee, who was thus led in triumph to the old crab; (a nick-name given to the agent for American prisoners of war, who resided near the prison.) He was very old and ugly, and used to creep over the ground not unlike a large crab. He was also very boisterous and ill-natured towards all of us, and in the sequel the reader will perceive, that to this was added cruelty and revenge. These peasants or country people, had five pounds sterling for taking up an American who attempted to make his escape; but they obtained only half a guinea for securing a French prisoner.* The first two months of my imprisonment here, I received from the hands of the Rev. Mr. Wren, every Monday morning, two shillings and six pence sterling per week, during which time I made out to live pretty comfortable, but when this source was gone, and no longer existed, which was soon after the fact, I lived truly very miserable, not having any more provisions and small beer during the twenty-four hours than would serve for one meal: this allowance was dealt out to each prisoner, being but three-quarters of what was allowed to common prisoners of war; this however our good friends, the English, even thought too much for rebels: I say our small pittance of provisions was dealt out to us every day at twelve o’clock; mine I used to destroy, or rather devour it at one meal, and not have enough to satisfy the cravings of hunger.

Now it was that I felt the disagreeable feelings of going part of the time half starved; and have often picked up bones in the yard and begged others without the walls of the prison, of people who lived near thereto; with these, by digging out the inside of them with a sharp pointed knife, I have partly satisfied the severe craving of an hungry appetite, which have often tasted to me more delicious than anything I have ever tasted since my liberation from this dismal confinement. Great numbers of the country people made it a custom to come and see us every day; but more particularly on Sundays; sometimes they would amount to a thousand and upwards: and on some of those days, many of which would make use of the following expressions, at the same time observing us very attentively: ‘Why, Lard, neighbour, there be white people; they taulk jest as us do, by my troth; thare’s a paity such good looking paple shou’d be troused up by our grate men, &c. (Troused =hanged.)

One day the following inhuman action took place here; an officer who mounted guard over us with his men, to the number of about an hundred, and who it seems were determined before they were relieved, to be the death of some of the rebels, as they expressed themselves to this effect to one of the turnkeys, who afterwards told it to one of us. Accordingly, to make some pretence, the officer, who I think was a captain, went into the guard-house and got a red hot poker, with which he fell to burning the American prisoners’ shirts, which they had hung upon the pickets to dry. It may be well here to observe, that the owners of these shirts had not a second to their backs; so that they begged the officer in a very civil manner, not to be so cruel as to burn all the shirts which they had; he would not however listen to their entreaties, but kept on his villainy. The American prisoners seeing this, ran to the pickets, and snatched away their shirts (but without making use of any abusive language), which so enraged this son of old Beelzebub, that he ordered the sentinel to fire his musket in among us, who instantly obeyed, and killed one man dead, and wounded several; at this time there were not less than three hundred Americans in the yard. This done, he ordered the guard to parade and fix their bayonets; they then rushed among us and drove us into prison and had the doors locked and barred, to prevent a revolt of the prisoners. The next day a jury was summoned, who met at the old crab’s dwelling-house, and after some deliberations, gave in their verdict manslaughter; although it was proved by more than twenty witnesses, who were inhabitants of Gosport, that the sentinel who committed this murder, after having discharged his piece, loaded it in an instant, and threatened to fire upon us again if we did not shut our mouths; thus ended (to the shame and confusion of the British character) this tragical event. Soon after this, Mr. Hartley,* then a member of the British parliament, a very plain man,. and who was said to be a great friend to the Americans, came to see us, talked familiarly with us, and gave us encouragement of our being exchanged soon: this was about the middle of November, 1778; but we put so little confidence in what he told us, that we imagined he only did it to amuse us, having so often heard such kind of stories from people who came to visit us. The hardships we had already experienced, and the thoughts of remaining in close confinement, perhaps for years, wrought so powerfully upon us, that we came to the determination of (the only way in our power) digging out. Accordingly, as we were shut into the prisons from sunset to sunrise, we occupied ourselves in the night, when all around was quiet, in undermining the prison walls in order to effect our escape, which proved effectual to great numbers: however, many who attempted this mode of escape, especially such as had not money enough to bear their expenses as far as London, a distance of about seventy-five miles, were taken and brought back to their old confinement; but were obliged to suffer the extra punishment of lying in the black hole* forty days and forty nights: (as long as Satan was suffered to tempt our Saviour.) In this place the American prisoners were allowed nothing but bread and water to subsist upon; many nevertheless, succeeded in making their escape even from this place by digging out, and crossing the channel to France, in small boats called wherrys. Those who had continued in the black hole till the expiration of the forty days, were allowed the liberty of the yard as before; being first entered upon the Agent’s books as deserters, and not to be exchanged till the very last. This was a great mortification to many, as will be seen in the end; for some of them, in consequence of their desertion, remained here prisoners of war three or four years thereafter: in fact, a few of them were not released from prison until the peace.

It will not, perhaps, be here amiss to mention what was done with so much dirt and stones, taken out of the great number of holes dug by the prisoners; which I will inform the reader, so far as has any relation to those under the prison where the officers were confined, and where I was. The dirt was partly lodged in an old stack of chimneys nearly in the centre of our prison; the fire-places below having been for years before stopped up, and we were lodged upon the second and third floors. The chimney aforesaid being white-washed, we used when our work was finished for the night, to paste a piece of white paper over the hole where we emptied the dirt into the hollow of the chimney. The dirt, &c., was put into small canvas bags, by those who were employed in digging under ground, and from thence passed from one to the other until it was at the place of deposit, where it was emptied, and then passed back to be filled again, where the diggers were at work. This kind of work began generally about 11 o’clock at night, when all was still excepting the sentinel, who would from time to time cry, `All’s well,’ and last till about 3 o’clock in the morning; at which time the hole in the chimney was closed as before related, and all of us would retire to rest. After a while the chimney was filled with dirt and stones; however, we soon found another place to deposit what we took out of the holes: this was in the garret of the prison, underneath the floor. It was lathed and plastered, through which we made a hole large enough for a man to get through into the garret, here we put several cartloads of dirt and stones, and the hole was secured in the same manner as the one before mentioned in the chimney.

In the prison where the American officers were confined was a number of French officers, who had been taken in the American service, two of whom were tolerable scholars, and amused themselves in teaching the Americans the French language.

I had myself acquired a considerable smattering of it before I left the prison; so much so, that I could converse with the French gentlemen who were our fellow prisoners. In the other prison, where the subaltern officers, seamen and other Americans were confined, there were regular schools kept, in which the masters taught reading, writing, arithmetic, and navigation. Numbers of the Americans,* who, when they were captured by the English and shut up in Forton prison, did not know how to read, and many others sides of the hall and in two rows of posts, about eight feet from the sides, to which our hammocks were suspended in the night; but during the day, they were hung up to the walls on each side; this made room in great plenty for walking and other kinds of exercise. The hammocks, to each of which was added a king’s rug (cover laid) a straw bed and pillow of the same kind, furnished each prisoner, at the King’s expense; these had generally been before used in hospitals, and on board of prison-ships, and were full of nits and Lice so that in fact we might have been called a lousy set of fellows; and the first thing to be seen every morning as soon as it was light, were naked men sitting upon their breach, in their hammocks, lousing themselves. Could we have obtained only the eighth part of a farthing for every louse so killed, from the government, and the money punctually paid us every day, we should have left prison as rich as Jews! One circumstance which occurred during my confinement here ought not to be forgotten; several of the prisoners were taken suddenly sick and removed to the hospitals; some of these died with strong symptoms of having been poisoned. This created a general alarm among the prisoners; some of whom believed the same game was playing here, as had been done on board the old Jersey, a prison ship near the city of New York; there held by the British, and on board of which ship, we had heard that thousands of our countrymen had died.* Various conjectures were agitated from whence the cause of this sudden and mortal disease had originated; and after a succession of trials, assisted by several physicians and surgeons who were among us, the poison was traced, and found in our bread; by dissolving which, we found quantities of glass pounded fine. Will any one who is ever so great a stickler for the British King and government and who has been acquainted with this circumstance, have the arrogance to say anything more about British humanity?

A regular complaint was now lodged by the Americans to the proper authority, and some enquiry made; some laid the blame to the-agent, he to the baker, the baker to them who furnished him with materials, with which he made his bread; and here this atrocious and murderous transaction ended. However, it is hoped by the compiler of these sheets, that this, as well as the conduct of the British relative to the old Jersey, will be had in eternal remembrance by the citizens of the United States, so long as the British shall exist as a nation!!! The humane and kind treatment of one person towards the American prisoners, however, ought to be universally known in the United States. I mean an English clergyman, by the name of Wren.* This good man, at the time, lived in Gosport, not far from Forton prison. His house was an asylum for the Americans who made their escape from confinement; and every one of these, if they could once reach his abode was sure to find a hiding place, a change of wearing apparel and money, if they were in want of it, and a safe conveyance to London, where they would consider themselves in perfect safety; as they could at any time go from thence to France, by the way of Dover and Ostendt. And in order to more fully illustrate the character of this Rev. gentleman, the reader is informed, that before the declaration of independence by the American Congress, large sums of money were subscribed by individuals in England for the benefit of the American prisoners, who were then confined in different parts of that country. The subscription, at one time, amounted to eight or ten thousand pounds sterling; towards which it is said, the queen gave one thousand guineas out of her private purse. This source soon dried up; for no sooner had the declaration of independence arrived in England than the subscription before spoken of ceased altogether. A committee of the subscribers chosen for that purpose had appointed a person at, or near each prison, where the Americans were confined, whose duty it was to distribute the money among the prisoners, according as they should deem to be right and just. Mr. Wren was the one appointed near us; and I believe he exercised the trust reposed in him, with punctuality. He made it a part of his duty to visit us once a week during my continuance here, and was in the habit of calling us, ‘my children.’ Besides, when the subscription fund was entirely gone, he used to go round the neighbourhood, and even where he was not known, to beg clothes and money for us. Often have I experienced this good man’s bounty. Frequently some bad characters among the Americans, would accost him with abusive and insulting language, if he did not supply all their wants: his only reply would be, “have a little patience, my children, and I will endeavour to bring you the next time I come, whatever you are most in need of”.

At length my deliverance from captivity drew near: an exchange of American prisoners was in contemplation; and the Rev. Mr. Wren assured us it would take place in a few days; and as this desired event approached the days and nights seemed to grow longer, and the time more irksome. In short, in the contemplation of which my heart leaped for joy, and my spirits raised above the power of description.

The long looked for day at last arrived; a day which I shall never forget: it was on the 2d of June, 1779, in the afternoon, when the agent’s clerk came into the yard and informed us, that one hundred and twenty of us were to go on board a cartel the next morning, in order to be sent to France. He then called over the names of that number, and I found myself included, being the hundred and eighteenth upon the list. And after he had read to us, with an audible voice, his majesty’s most gracious pardon, he told us that we must hold ourselves in readiness to go on board of the cartel, then lying at the Key, on the west side of Portsmouth. Never I believe was joy equal to what I now experienced. Accordingly, the next morning about eight o’clock, we who had been called over the day preceding, were again called’ upon to answer to our names, and were paraded in the yard: the rest of the American prisoners, amounting to about four hundred and eighty in both prisons were not permitted to mix with us, and not suffered to come out of their confinement till we began our march, which commenced about 10 o’clock, in company, or rather escorted by about forty British soldiers and a number of black drummers and musicians, who beat up the tune of Yankee Doodle, which they continued playing, till we arrived at the place of embarkation. We left behind several poor fellows, who had been prisoners three years and upwards; and as for myself, I had been one only about thirteen months; therefore, it is easier I think, for anybody to judge than to pretend to describe the mortification of those who had been so long in confinement, on seeing us thus about to taste the sweets of liberty! Methinks some of them would be led to exclaim, 0 Liberty! 0 my country! On our march through the town of Gosport, the streets became crowded with people; some wishing us safe to our desired homes; others crying out, that we were a set of rebels, and that if we had had our deserts we should have been hanged: these exclamations were repeated with loud Huzzahs.

The Reverend Thomas Wren, a Presbyterian minister, was awarded a Doctor of Divinity degree in 1783 for services to American prisoners at Portsmouth. Forton prison was staffed by a keeper (agent), his clerk, three turnkeys, a steward, a doctor, cooks, labourers and a varying number of military guards. Wren quickly came to the aid of the captured rebels. He made regular visits to the prison and was allowed to distribute small sums of money to captives who were in special confinement. He managed to source financial contributions through local friends and obtained donations of clothing. He provided prisoners with items such a medicine, often from his own income. The narratives of several prisoners acknowledged the help provided by Wren. One prisoner, Timothy Connor, noted that Wren kept alive the inmates hope for eventual repatriation.

Prison life was tedious and boring. men were given almost absolute freedom in determining the use of their free time. They organised regular schools where the prisoners were taught reading, writing, arithmetic, navigation and french. They were allowed to write letters, keep diaries and journals and purchase books. They also became friends with many of the guards resulting in perks such as local newspapers. The death statistics at Forton from June 1777 to November 1782 show that only sixty-nine Americans died, 5.75% of those confined.

The escapes from Forton between 1777 and 1782 were 536 men. The prison at Forton was officially closed in the Summer of 1783. The American prisoners were released with the words ‘You all now have received His Majesty’s most gracious pardon.

An American report of 1817 described the military Prison at Forton thus: ‘Forton-prison hospital, is intended for the accommodation of French prisoners of war. Its officers (medical) belong to the navy. This hospital is situated near to the town of Portsmouth ; it has a surgeon, a dispenser, four hospital-mates, a clerk, a steward, and a matron.’

As a result of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, a number of French prisoners were housed in hulks floating in Portsmouth Harbour with many more in Forton (Fortune) Prison. A letter to the Home Secretary dated 20 September 1892 concerning French prisoners held at Forton lists a range of men that were incarcerated there with ages ranging from 29 years to 76 years. Another letter dated 1793 lists a capacity for 2000 prisoners there.

The Morning Post reported on July 24 1807 that On the evening of the 22nd July, 1807 This afternoon a fire broke out on the old buildings of Forton Prison, near Gosport. These buildings are undergoing a thorough repair for the accommodation of French prisoners, and the fire is supposed to have been occasioned by the boiling over of a quantity of pitch in the workshop. Nearly the whole buildings are consumed, and the fire still continues to rage with violence. According to the local newspaper the East Kent Malitia together with the Gosport Volunteers were very active in guarding the prisoners and assisting them to extinguish the fire. The whole range of buildings on one side of the prison were destroyed. However during the proceedings the gates were thrown open and it was reported that a number of prisoners took the opportunity to make good their escape. During muster the following day they were found to be present.

Dr. White writing in A History of Gosport states that: Another threat to the citizens of Gosport came from the numerous attempts at escape by the prisoners. Sometimes they were successful, at other times the fugitives were caught and executed. In 1812 three prisoners on parole got away from Forton and made their way down to the harbour. There they hired a waterman named George Brothers, telling him they were sailors making their way back to their ship in Spithead. Once they got outside the harbour they offered him a bribe to help them but he refused and tried to signal his plight to nearby ships in Spithead. The fugitives stabbed him and threw his body overboard. The incident was seen from the shore and boats set out in pursuit. Eventually, however, they were overtaken and subsequently executed at Winchester.

In April 1850 it was reported that the new prison at Forton was complete. The Standard Friday, April 12, 1850 described it thus:

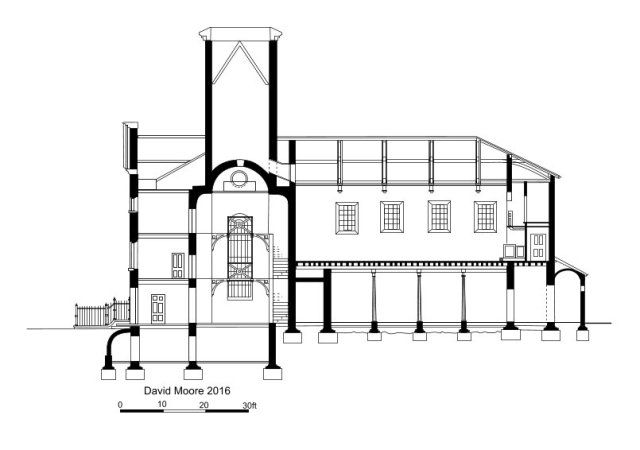

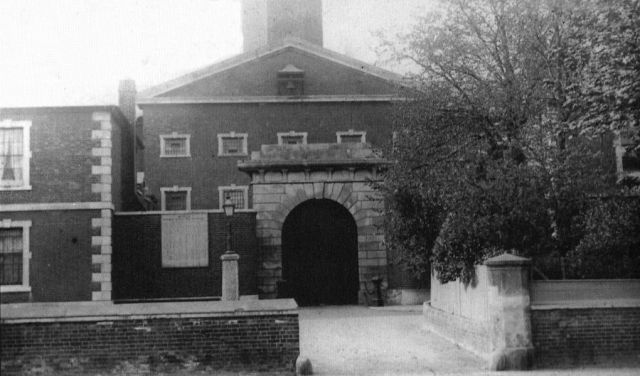

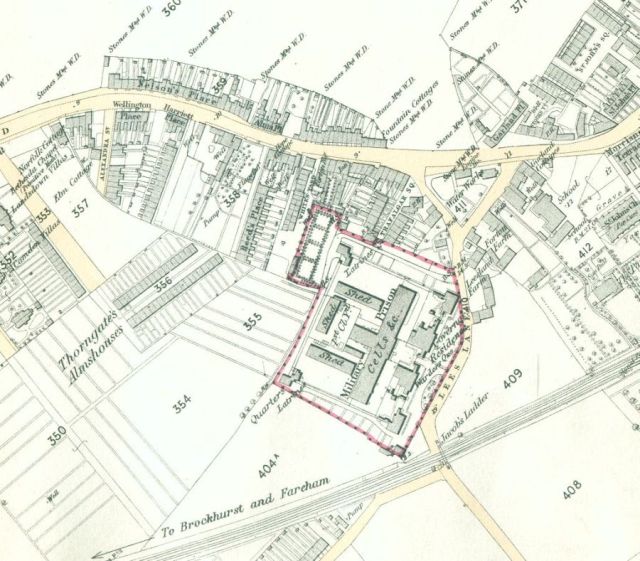

The new military prison at Forton. Gosport, is now completed, and in about a fortnight the establishment now occupying Southsea Castle will be moved over; it consists of a governor, Captain J. Curtin (late 40th Regiment), chaplain, the Rev. Mr. Dennis; a surgeon, Mr. Dowse; a schoolmaster (not yet named); with about 17 or 18 warders, The new prison will contain about 130 prisoners, each with a separate cell. The cells are capacious, airy, and well lighted by a small corrugated glass window, placed high up. The glass admits light freely, but is impervious to sight, and a small pane can be opened by the prisoner, to admit air, if he requires it- The cells, and indeed the whole building, is kept perfectly warm, by hot air pipes, that run under the floorings. Each cell is provided with a bell-pull, which strikes a gong, and the act of pulling the bell throws out an indicator that points to the warder the cell from which the bell has been rung. The building is three stories high, the cell doors face each other in three tiers, with iron verandahs running along. The centre or aisle between the doors is lighted from the top by a glass roofing. The lower tier of cells contain the solitary and dark prisons for punishment, but these are also warmed by hot-air pipes, and are well ventilated. Four baths for the use of the prisoners also occupy the basement, and in each there are places for washing, shaving, and a number of water-closets. The food is hoisted up from the furnace-room through a trap-door in the floor, and a railway then conveys it to the door of each cell. At the back of the prison is a capacious chapel, and underneath the chapel room is a large school-room. The prisoners are generally in three classes, and within the walls are three class-yards. The first class prisoners are treated best. They have their bed every night; they do the work of the prison, carry coals, &c. The second class have their bed every other night. They work at moving 24-pound shot so many hours a day in three-class yard, and have a capacious shed to keep them from the effects of bad weather. The third class are the worst-behaved men. They have their beds only one night in three, or otherwise, at the discretion of the governor. They work in third-class yard during the day with 24-pound shot, and on misbehaving are ironed and confined in the dark cells Every prisoner comes in first as a third class prisoner, but is moved up according to the nature of his crime and his behaviour in prison. The prison has been erected at the expense of £30,000, and is a most perfect thing of its kind; and from the many comforts it appears to contain, seems a prison where confinement is the only punishment.

The prison was constructed of red brick with stone dressings and roofs of slate. Centre of the main cell block was a 70ft tall octagonal foul air vent, which could be seen for a considerable distance. The entrance to the barracks was from Lees Lane and was protected by a small drop ditch and drawbridge. The perimeter wall was loopholed for local defence. A guard house stood outside the prison at the south western corner close to the Gosport railway-line. Warders’ quarters were situated at the four corners of the Barracks and on the west side of the entrance. To the east side of the entrance was the Chief Warder’s Quarters and the Governor’s quarters.

The convict’s cemetery was next to the military cemetery, on Forton Creek, north of the Forton Barracks.

A press report in 1882 indicated that the Military Prison had 160 prisoners with 10 unarmed warders. The Governor was at that time Major D.F. Allen.

In the early 1900s Forton Military Prison, as indicated on the 1906 plans, was changed to a Detention Barracks under a Commandant instead of a Governor.

The barracks became surplus to requirements some time after 1926 and was demolished in stages starting with the interior buildings. By 1933 the front of the prison with the Warders’ quarters, and two of the large sheds remained.

In 1939 Gosport builder Vic Hutfield bought the prison site and began demolishing the buildings. He used some of the bricks to build a bungalow for himself, Chilworth, on the Lees Lane site as well as other buildings for rent.

Some remains of the old Forton Detention Barracks are on display in Gosport Discovery Centre.

Sources:

Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the High Court of Chancery: 1725 Pratt versus Jackson.

The Memoirs of Nathaniel Fanning 1778 to 1783: by Nathaniel Fanning

Thomas Wren and Forton Prison: by Sheldon S. Cohen

Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography: Thomas Wren ministering Angel of Forton Prison

Yankee Sailors in British Gaols: Prisoners of War at Forton and Mill, 1777-1783: by Sheldon Samuel Cohen

The Treatment of American Prisoners of War during the Revolution: by William R. Lindsey

A Girl called Thursday: Lillian Harry (Fiction)

British Supporters of the American Revolution, 1775-1783: by Sheldon Samuel Cohen

Yankee Sailors in British Gaols: Prisoners of War at Forton and Mill, 1777-1783: by Sheldon Samuel Cohen

The Morning Post: Fire at Forton Prison Friday July 24th 1807

A treatise containing a plan for the internal organization and government of marine hospitals, in the United States : together with observations on military and flying hospitals, and a scheme for amending and systematizing the medical department of the Navy (1817)

Gosport Records No.12: Forton Barracks 1807 -1923: by Dione Venables

A History of Gosport: by Dr. White

Howlett plans in Portsmouth library.

National Archive Plan of the prison dated 1815 MPD194

Vic Hutfield website

Original page created by David Moore.