These documents, originally belonging to the Office of the Ordnance at Portsmouth Dockyard, give a glimpse of the workings of said office for the 100 years between 1695 and 1797. They include instructions from the Tower of London, where the Ordnance Office was based, to the storekeepers at Portsmouth, receipts, and bills from artificers such as the coopers, smiths, armourers, carpenters, and waggoners, and demands from regiments of the Navy, army, forts, and castles in the Portsmouth area and beyond for powder shot, small arms, and other small stores. The conversation is somewhat one sided as we only get to see those documents coming into the office at Portsmouth, and not those that were sent in reply.

The language they used was a little different to our own, their use of words, and even the forming of letters was different, ‘S’s, ‘C’s, ‘F’s and ‘I’s can be particularly difficult to recognise, spelling was flexible, for example we may see something like: ‘ben trewley pe formed’ for ‘been truly performed’. In transcribing the documents, the original spellings have been maintained and should not be regarded as spelling mistakes, but simply the way the words were spelt at the time by the individual. If the words are said as written, their meaning usually becomes evident. Unfortunately, we occasionally come across script that defies understanding.

Writing materials were expensive at the time, so contractions were very commonplace to save on ink and paper. For example:

the letter ‘Y’ was frequently used as a contraction for ‘th’ so we see ‘Ye’ in place of ‘the’ or ‘Ym’ in place of ‘them’ etc. (The ‘Y’, however, was pronounced ‘th’. Contractions were to save ink, not to change pronunciation.). The letter ‘Y’ is actually an Old English (Anglo-Saxon) rune known as ‘thorn’, and pronounced ‘th’. As well as ‘ye’ (the), it also commonly occurs as ‘yt” (that).

The likes of: Portsmo, Weymo, or Plymo for Portsmouth, Weymouth and Plymouth respectively were also used.

Months of the year:

There are two issues with the months of the year. At the time of the majority of these documents there were two calendars that people might use: the Julian, or the Gregorian. In the Julian calendar the year started on Lady’s Day (25th March) and so dates in the months of January, February and March were often written as, for example: 21st February 1708/9, for which we would now use 21st January 1709.

The second issue is regarding contractions used for months at the end of the year. To understand the contractions used for months, one needs to understand how our calendar has evolved. We currently use the Gregorian Calendar, but it is based on the old Roman Calendar which, although having 12 months, only the last ten of them, from March to December, were given a name. The winter months, when nothing was done because of the cold weather, were ignored and unnamed. So we had March (Martius), May (Maius), June (Junius), April (Aprilis) and then the rest of the months were numbered: Seventh (September) giving us 7ber, eighth (October) giving us 8ber, ninth (November) giving us 9ber, and the tenth (December) giving us Xber.

An interesting contraction was the use of an elaborate capital ‘P’ for ‘per’ or ‘pair’. It was sometimes also used within a word such as ‘reP’ to give us: ‘repair’. Where used to indicate ‘per’ it would have meant ‘by order of’, or ‘on authority of’. This character was also used to indicate ‘Packet’, a fast sailing vessel.

Christian names were routinely abbreviated such as Archd for Archibald, Jno for John, Jonth for Johnathan, Edwd for Edward, Wm for William etc.

Occasionally a word might be contracted where one might not expect it. For example: in one document we see the word ‘Northumberland’ become ‘North berland’ with a long dash above the word to indicate that this is a contraction.

In the 100 years spanned by these documents the spelling of words can be seen to gradually change from almost wholly phonetic to a more ordered style. For example: ‘Oyle’ and ‘Wyre’ became ‘oil’ and ‘wire’. ‘Att’ and ‘Shott’ became ‘at’ and ‘shot’. There can be seen a marked contrast between the letters from The Tower of London (headquarters of the Office of the Ordnance), written by clerks, and the bills, notes and accounts submitted by the artisans, master gunners, ships masters &c. written in their own hands.

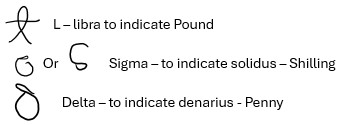

Weights and measures were also less recognisable; inches, feet, yards, fathoms, cables, hundredweights, quarters all had unfamiliar abbreviations and symbols to denote them. For example: where we use the ‘£’ sign (a capital ‘L’ with a strike through it) to denote the pound sterling, ‘lb’, or ‘li’ a contraction for the Latin ‘Libra’, may have been used, or a symbol loosely based on ‘lb’. Whereas another symbol altogether, an ‘l’ with a strike through it, was also used to denote a pound weight.

For pounds shillings and pence we see the use of symbols based on the Greek and Latin alphabets for Libra, Solidus and Denarius.

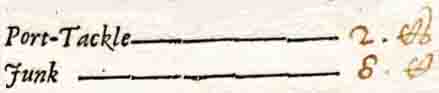

Typically, weights were measured in Tons, Hundredweights, Quarters and Pounds. For hundredweight (cwt) a symbol based on an elaborate capital ‘C’ was used, C being the Roman letter for 100. For a quarter they would use ‘Qr’ or the cwt ‘C’ symbol followed by a small ‘r’. The example below demonstrates the use of the symbols: we can see: Port-Tackle – 2 cables, and Junk – 8 hundredweight.

The Glossary’s Weights and Measures section will help with all of these symbols.

To add to our confusion, whereas we call the guns aboard a warship of this time ‘cannons’, only the very largest were so named, they were more rightly referred to by size, and given names such as minion, saker, demi-culverin, culverin, &c, so named after birds of prey, or referred to by poundage of shot: 6-pounder, 12 pounder, 18 pounder etc. Many other items mentioned will be unfamiliar, look in the Glossary for explanations of these.

Large and small items were referred to as extraordinary and ordinary (as seen when used to describe the trucks, or wheels, of a gun carriage), or ‘great’ and ‘small’.

The content and frequency of the documents give us an insight into the movement of ships in and out of Portsmouth harbour, the armaments they carried and the sheer weight of work that was carried out at the Dockyard. A simple phrase ‘you will take out her guns’ implies a huge task as a ship may have as many as 100 guns, each weighing several tons.

We are also given an appreciation of the infrastructure of the country at that time. Letters could be written in London in the morning, then be in Portsmouth before the end of the working day; not possible today. Stores were transported either by wagon or by sea, a journey not without its dangers: the weather and attacks on our ships in the English Channel being a real hazard prompting the building of the Portsmouth and Arundel Canal in 1823 to provide a safe means of transporting weighty stores by land. The canal ran through Portsmouth from Milton, following Locksway Road then on to Fratton where the railway has now been built on the old canal bed. Just before Portsmouth and Southsea railway station the canal then turned North to terminate at Landport where the junction of Arundel Street and Commercial Road is now. The canal was abandoned in 1855 when the seawater that it carried leached into the drinking water.

The majority of the documents are handwritten in ink on single sheets of parchment, or cartridge paper, but some are on fine paper, others are printed on heavy parchment. Those on parchment have been folded carefully, addressed and in most cases, sealed. On receipt, documents were generally date stamped with a ‘Bishop Mark‘. So named after Henry Bishop who as Britain’s Postmaster General from June 1660 to April 1663 introduced the date stamping of letters on receipt. The Bishop Mark endured until about 1790 when a more elaborate, sometimes less clear, replacement was introduced.

Documents were endorsed, usually with a brief precis of the content, on the reverse side. Many also have ‘Entd’ written in small script: one must assume that this indicated entry into a journal, or ledger. In transcribing the documents this has been reflected by segregating the format into three parts: The precis and date stamp, the address, and finally the content.

Signatories of the documents were, in the main, significant figures holding high office. These would have been very important people at the time. The likes of John Churchill (The Duke of Marlborough, the builder of Blenheim Palace and 6th great grandfather of Winston Churchill), Sir Thomas Frankland (2nd Baronet, of Thirkleby Hall in Yorkshire), and Christopher Musgrave to name but a few. Not to mention also Mr. John Hooper and Captain John Baxter who were the storekeepers of the Office of the Ordnance at Portsmouth for much of the period.

A number of documents titled ‘Declared Accounts: Ordnance’ lists many of these people and their salaries, together with expenditure for various services. I have found lists for the following periods: 1689-1692, 1711, 1713, 1714, 1716.

There were also the likes of Talbot Edwards, based at Fort Blockhouse in Gosport, Captain of Royal Engineers; famed for his engineering works in Gibraltar during the siege of 1704, chief engineer in Barbados and the Leeward Islands, who was later appointed Deputy Chief Engineer of Great Britain. These people had their parts to play. It must be remembered that, apart from these dignitaries, at the time of these documents, when most people were illiterate, anyone who could read and write was educated and so nobody appearing in the documents was insignificant.

We are at times given an inkling as to the character of some of the people. The forementioned Captain Talbot Edwards, for example, comes across as very abrupt and to the point in most of his demands for stores, seldom do we see him ask, and, unlike in others, we rarely see a polite ‘your humble servant’ before his signature. Was he just rude, arrogant, or unthinking? we shall never know.

It is also interesting to note the terminology used when the people refer to one another, one would not today see a man referring to another as ‘my dear’ nor expect to see a work colleague sign a business letter as ‘your loving friend’, but in the 1700s such terms were commonplace.

Many of the documents were sealed, but few actual seals remain as the wax would have been melted down to be recycled, so all we see is a pink mark on the paper where the wax was once attached. Two did survive: one with the seal of the Office of the Ordnance (three guns), and one other, appears to be a representation of a bust of Charles 1st ‘Carolus I’; curious as he was executed 70 years previously.

If he were still with us, I feel sure that the author, Patrick O’Brian (Master & Commander) would lap up the information contained within these documents. For anyone wishing to understand the period, the method of writing, terminology, or budding authors, these documents are a mine of valuable information.

The Life and Times Of The Office of the Ordnance In Portsmouth Dockyard During The 1700s

It was the Romans who first recognised the value of a large natural harbour that they called ‘Portus Adurni’, and they built a fortress at the top end where remains of their work have been found in the Fareham and Portchester areas. It is highly likely that they would have built watch towers and established some form of garrison near the harbour entrance on the Portsea and Gosport sides to prevent invaders from entering the harbour. In doing so communities would have built up around the garrisons paving the way for the busy communities that would follow.

Although dockyard facilities had existed in Portsmouth since the late 1100s, dockyards, as we know them today, really came into being in the 17th and 18th centuries, the first being at Chatham and Portsmouth, later others emerged at Plymouth, Deptford, Woolwich and Sheerness. They were used to moor ships of the Navy while they were not in use. Unlike today, the Navy were a fair-weather fleet and spent a lot of time in port. However, as time went on, ship building, and thereby seaworthiness improved, and the Navy expanded in the face of increasing duties imposed upon it.

Ships were built at Portsmouth from the late 1400s, but it was probably not until Henry VIII granted Portsmouth a charter did things really kick off. In 1510 the Mary Rose was built in Portsmouth. 1513 saw the beginning of the victualling yards to supply the Navy with food and drink. Necessarily, other facilities would be built to supply rope, timber, barrels, blocks, tackles and, of course, ordnance.

Enter Mr. Hooper & Co.

By 1680 Samuel Pepys had reformed the victualling standards of the Navy ensuring that crews were well nourished. By now the dockyard was expanding and by 1700 much of the dockyard would have been recognisable to us today. The Office of the Ordnance had its headquarters in the building that is now Portsmouth Registry Office at the north end of Burnaby Road. Some of the buildings in St James’s Street survive from the time of these documents as does St George’s Chapel in St George’s Square. oldmapsonline.org/compare allows us to compare today’s Portsmouth with the way it looked in the 1800s.

The gun wharf referred to in these documents was not inside the Royal Navy Dockyard of today, but was where the shopping area known as Gunwharf Keys now stands. the gun wharf was on the site from the 17th century until 1923 when it became HMS Vernon the Navy’s Torpedo and mining establishment which was there until 1986 when the land was sold.

This brings us to the documents belonging to the Office of the Ordnance which give us insight into the workings of the dockyard.

We are going to look at the scanned documents in some detail. Not every document will be commented upon, but that does not mean that those not commented on are of no interest; they all have a part to play in opening a window to the 1700s. Even from the briefest of notes on a scrap of fine paper we can glean nuggets of information that help to paint the bigger picture. From these we can piece together a view of life in and around Portsmouth Dockyard and beyond. We can visualise the hoys with their highly skilled masters, transporting stores to and from the ships at Spithead and other dockyards, ‘the danger of the seas expected’. From scraps of paper, we learn the names of these hoys, and their masters.

Now, click on the ‘Documents’ tab to view the actual documents. Start with the 1695-1709 page. The Glossary pages allow you to look up the ships, the people and the less familiar terminology. You can also download this information as an Excel spreadsheet.